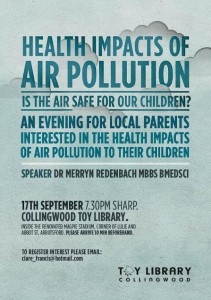

On 17th September 2014, a presentation on the Health Impacts of Air Pollution was held for concerned parents in the Collingwood area. Collingwood has some of the worst traffic in Melbourne but the air quality is not regularly measured. Keele Street Creche now has monitoring but it is unclear if any results will be released to the public before the election.

Dr. Merryn Redenbach from Doctors for the Environment spoke about the different types of air pollution and the different health impacts. She explained air pollution is particularly bad for children, whose lungs are still developing and breathe a lot more than adults as they run around more. The elderly, and people who already have heart and lung illness, and people living in areas of high pollution are the most vulnerable. Sadly, this usually correlates with lower socio economic groups.

One form of pollution of real concern is particulate matter. These are tiny particles, smaller than dust. The smaller the more hazardous. Australia only has limits for the largest particles known as PM10.

Australia has the slackest air pollution laws in the developed world. You’d have to go to India to find higher Sulphur limits. Many of the Australian limits are just guidelines and there is no evidence that says the limits represent a safe environment. When national standards were introduced in 1998, they were supposed to be reviewed in 3 years, that still hasn’t happened.

The US and Europe have been tightening air pollution laws, but Australia is still stuck in 1970s – despite considerable research showing that air pollution is far more hazardous than previously thought. The World Health Organisation has recently classified Diesel fumes as a class 1 carcinogen. So it joins asbestos and tobacco in terms of cancer risk. So much for diesel cars being clean.

Melbourne exceeded the very lax limits for the larger particle PM10 on 27 days in 2008. This is worse than any other city in Australia.

But the situation is far worse for the smaller PM2.5 particles. Australia has no compliance limit for these. There is only an advisory, which is regularly breached – though rarely monitored or published. Even our ‘advisory’ limit of 10ug/m3 is higher than the mandatory limits in the US(8) and Europe(7.5). Evidence is growing that these smaller particles are far more dangerous than larger particles. They travel further from the source and travel further into our blood stream. Our bodies have not evolved to protect the lungs from these tiny invaders.

There are both long term and short term impacts from exposure to air pollution. Deaths in Morwell are already much higher than ‘normal’ following the recent Hazelwood coal mine fire and scandalous advice from the EPA and Government that it was safe to stay. After the 2009 bushfires, the hospitals were crowded due to the poor air quality in Melbourne.

We also learned that the Alcoa power station in Anglesea has three times the sulphur emissions of the Hazelwood power station, but only generates one tenth of the power. This power station is less than a kilometre from a primary school. Given the Alcoa smelter has shut down and there is an excess of generating capacity, it is a disgrace that this power station is still operating.

Evidence is now strong that there is no safe lower limit. Even low levels of air pollution well below the legal limits have measurable health impacts.

The good news is that when pollution is reduced, it has an immediate and lasting effect. This was evidenced after Dublin banned coal burners and in Atlanta prior to the Olympics. The health improvements flowed into economic benefits that exceeded the cost of cleaning the air.

The other potentially good news is a proposal to tighten air pollution laws in Australia. Concerned citizens were urged to make a submission

- Proposed variation to the National Environment Protection (Ambient Air Quality) Measure in relation to the standards for particles.

- For talking points, visit Environmental Justice Australia and review their submission guide and Clearing the Air paper.

- Submissions due October 10 2014.

In summary, we need better monitoring, of both ambient air and large emitters. We need transparent reporting and real time alerts. We need to replace information guidelines with enforceable standards and real penalties, and we must legislate protection from exposure for the most vulnerable groups. All major projects should have an independent assessment of air pollution health impacts.

Clare Francis, who organised the talk, provided some practical tips to mothers on how to reduce exposure by not driving behind buses or trucks, not walking along busy roads, closing the air vents when driving through a tunnel and turning of the diesel engine instead of idling outside the primary school waiting to pick up the kids.

The meeting was also addressed by local residents Dr Robyn Schofield, lecturer in atmospheric chemistry and Dr Karen M. Kiang a paediatrician who joined the dots between climate change and child health.

“The future is not somewhere we are going it is somewhere we are creating”. – Ian Lowe